Case Name: Korematsu v. United States

Case Number/Citation: 323 U.S. 214 (1944)

Facts of the Case:

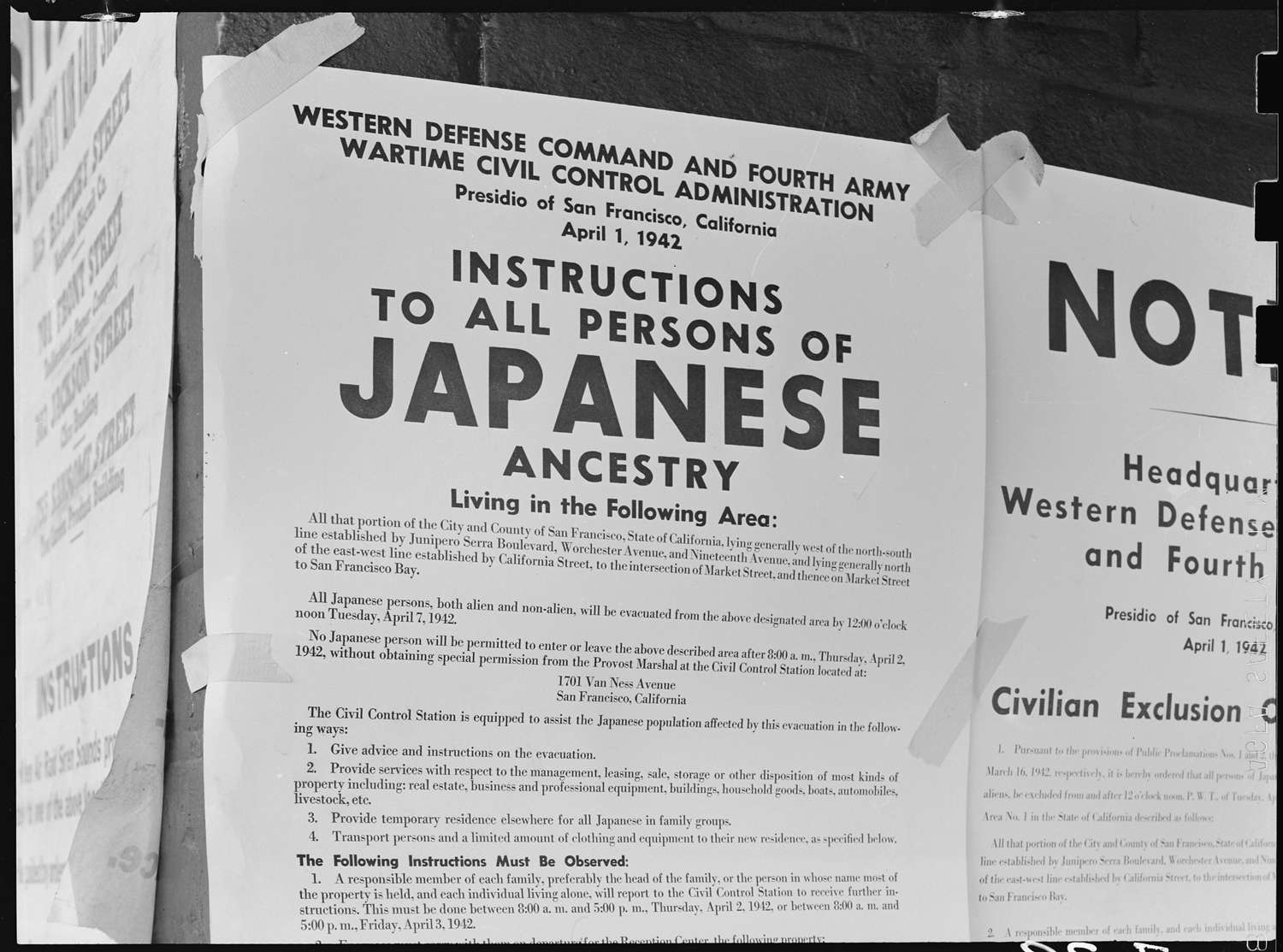

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which forced individuals with Japanese ancestry to relocate into camps in the wake of the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and Congressional action to go to war. Additionally, the Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34 ordered all individuals with Japanese ancestry should be excluded from military areas which included the West Coast that gone into effect on May 9, 1942. Breaking the law was a criminal misdemeanor that faced fines of up to $5,000 and/or up to 1 year in prison. Fred Korematsu, in the wake of the new orders, refused to relocate and instead stayed in his residence. Korematsu was subsequently arrested and convicted in federal district court. Korematsu attempted to appeal his conviction, arguing that the Executive Order violated his 5th Amendment rights. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s decision and his conviction stayed. Korematsu appealed to the Supreme Court where the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

The United States has standing, because such a legal challenge would affect the government’s ability to enforce the law. Korematsu also has legal standing because he is directly affected and injured by the Executive Order since he was arrested and convicted. This case concerns the 5th and 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

Question:

Did Executive Order No. 9066 which forced individuals with Japanese ancestry to relocate to camps violate the 5th Amendment and 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause?

Conclusion:

No, the 6-3 majority held that it was permissible for the government to relocate Japanese Americans in times of war. Writing for the majority, Justice Black argued that the legal challenges are based on the Court’s conclusions in an earlier case in Hirabayashi. The majority analyzed and used military reports that argued that there were those Japanese Americans who “refused to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States” and that some “requested repatriation to Japan.” The majority also validated the military’s argument that the need for such action was important and that it was “impossible” to investigate individually who was committing espionage. And while the majority acknowledged that curtailing a single racial group’s civil rights “are immediately suspect”, the Court also acknowledged the “hardships of war” and that the military’s interest to protect “threatened danger” is far more compelling than the “compulsory exclusion of large groups.”

Writing for the dissent, Justice Murphy argues that the executive order is an example of a “legalization of racism.” Justice Murphy also writes that the majority erred in that the law failed to meet the compelling interest standard. To further his reasoning, Justice Murphy argues that the military has not even reasoned to treat Japanese Americans on an individual basis, “as was done … [to people] of German and Italian ancestry…”. Likewise, the Justice pointed out that there was no evidence to show that such individuals were disloyal. Justice Jackson also wrote another dissenting piece, arguing that the Executive Order also violated the attainer of treason in the Constitution. He argued that the law made an innocent person a criminal because the convicted person is a “son of parents …[which] belongs to a race from which there is no way to resign”.

Major doctrine:

The Supreme Court’s decision to affirm the lower court’s ruling validated the government’s authority to infringe certain liberties in times of imminent war. In Korematsu, the government’s compelling interest in national security at times of war may skirt certain constitutional liberties.