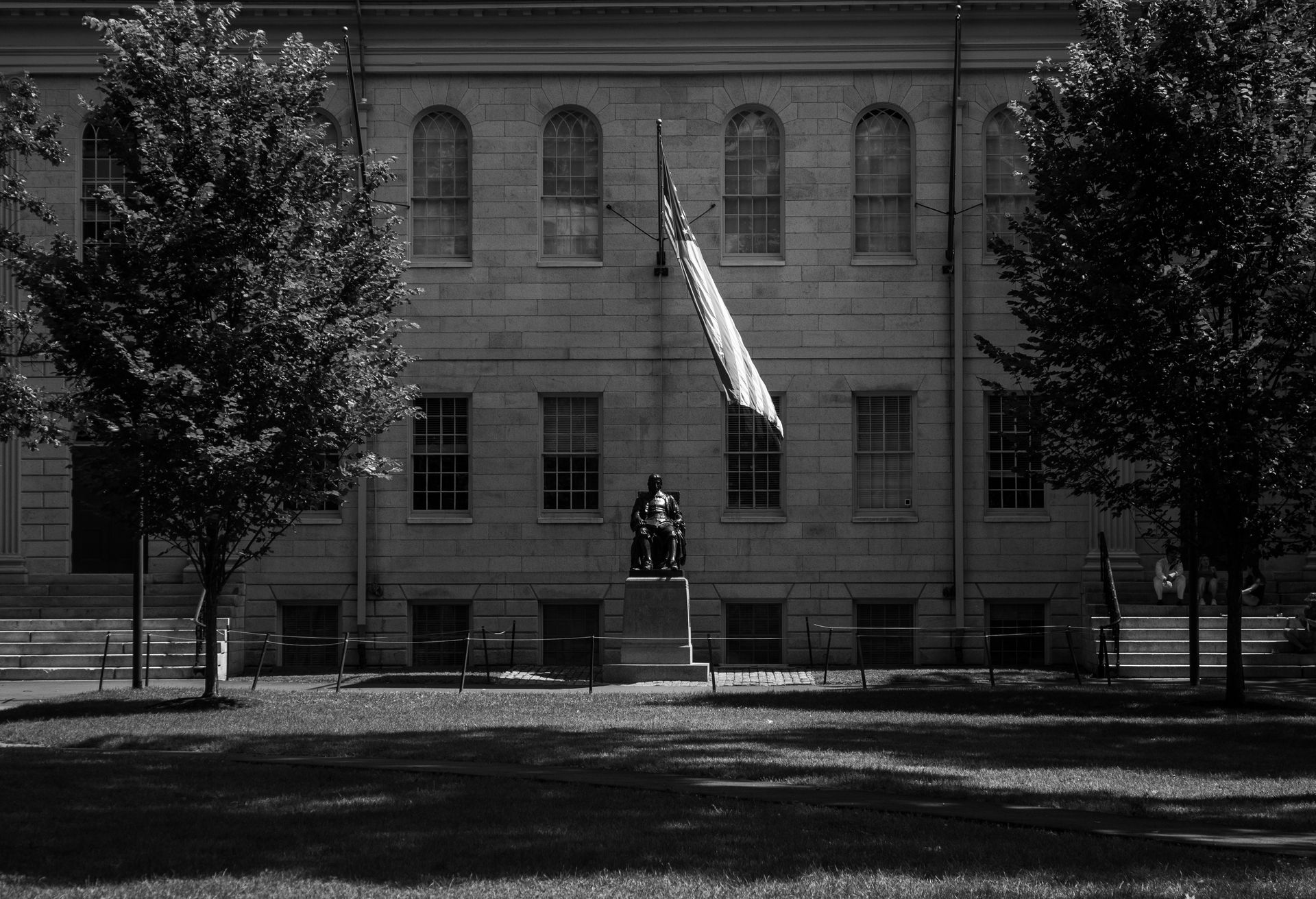

In a significant ruling this week, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that Harvard University and the University of North Carolina (UNC) violated the U.S. Constitution with their race-conscious admissions policies. The cases of Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. UNC resulted in split decisions, with the Court ruling 6-2 and 6-3, respectively. The Court’s majority opinion ruled that using race as a determinative factor in college admissions violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. This ruling, contained in a 273-page decision, effectively bans race-based preferences in both public and federally funded private institutions. The legal battle, which began in 2014, has cost Harvard and UNC over $27 million and $25 million, respectively.

“Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it,” Roberts wrote.

Admissions Policies

During the oral arguments, Harvard and UNC suggested that their race-based admissions programs would only end once there was "meaningful representation and meaningful diversity" in the student population. “At Harvard, each full committee meeting begins with a discussion of ‘how the breakdown of the [current year] class compares to the prior year in terms of racial identities’ … and ‘if at some point in the admissions process, it appears that a group is notably underrepresented or has suffered a dramatic drop off relative to the prior year, the Admissions Committee may decide to give additional attention to applications from students within that group.’”

Chief Justice Roberts argued that Harvard and UNC "turn that principle on its head" by linking the termination of college’s race-conscious admissions to achieving certain percentages of racial groups. He noted that such college admissions programs "effectively assure that race will always be relevant" and that the ultimate goal of eliminating race as a criterion "will never be achieved."

History

Since the 1970s, educational institutions have implemented race-based preferences and quota measures to enhance student diversity, following the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

This led to legal challenges, including Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, one of the earliest Supreme Court cases that banned racial quotas in college admissions. However, the Court's opinion in Bakke deemed it “constitutionally permissible” for colleges to consider race as a factor in admissions.

Subsequent cases, such as Gratz v. Bollinger, Grutter v. Bollinger, and Fisher v. the University of Texas (Fisher I & II), legitimized the compelling interest in diversifying the academic student body through affirmative action and in where affirmative action did survive judicial scrutiny.

In Grutter v. Bollinger, the Court “endorse[d] Justice Powell’s view that student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions.”

The Supreme Court in Grutter, on the other hand, limited the use of race-conscious admissions in that it had to pass strict scrutiny and acknowledged two prominent dangers.

First, the Court argued that admissions programs could not “operate on the belief that minority students always or even consistently express some characteristic minority viewpoint on any issue.”

Secondly, the Court warned that “race would be used not as a plus, but as a negative—to discriminate against those racial groups that were not the beneficiaries of the race-based preference.” As such, race-based preferences would “unduly harm nonminority applicants.”

As a result of those risks, Grutter posed a final limit on affirmative action, expecting that “in 25 years, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.”

Until this recent ruling, Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) protected 50 years of affirmative action in American college admissions, including 20 years after the decision. Now overturned, colleges across the U.S. are scrambling to revise their admissions policies.

Understanding Strict Scrutiny

The 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause provides remedies for classified protected classes who face unequal treatment under the law. The Equal Protection Clause has historically been cited in cases where discrimination against a certain group of people exists.

Discrimination based on race is subject to strict scrutiny by the Supreme Court. In SFFA v. Harvard, where race was a protected “suspect” classification, the Court applied strict scrutiny to assess whether affirmative action served to “further compelling governmental interests,” and whether the use of race was “narrowly tailored”—meaning “necessary”—to achieve that interest.

“One of the principal reasons race is treated as a forbidden classification is that it demeans the dignity and worth of a person to be judged by ancestry instead of by his or her own merit and essential qualities … when a university admits students “on the basis of race, it engages in the offensive and demeaning assumption that [students] of a particular race, because of their race, think alike” - Chief Justice Roberts, SFFA v. Harvard

Harvard and UNC's Interests

The Court cited Harvard and UNC’s expressed interest in promoting their affirmative action policies. “Harvard identifies the following educational benefits that it is pursuing: (1) training future leaders in the public and private sectors; (2) preparing graduates to adapt to an increasingly pluralistic society; (3) better educating its students through diversity; and (4) ‘producing new knowledge stemming from diverse outlooks.’”

“UNC points to similar benefits, namely, (1) promoting the robust exchange of ideas; (2) broadening and refining understanding; (3) fostering innovation and problem-solving; (4) preparing engaged and productive citizens and leaders; [and] (5) enhancing appreciation, respect, and empathy, cross-racial understanding, and breaking down stereotypes.”

Robert writes that while those interests are “commendable,” he argues such interests “are not sufficiently coherent for purposes of strict scrutiny” and are “inescapably imponderable.”

Students For Fair Admissions

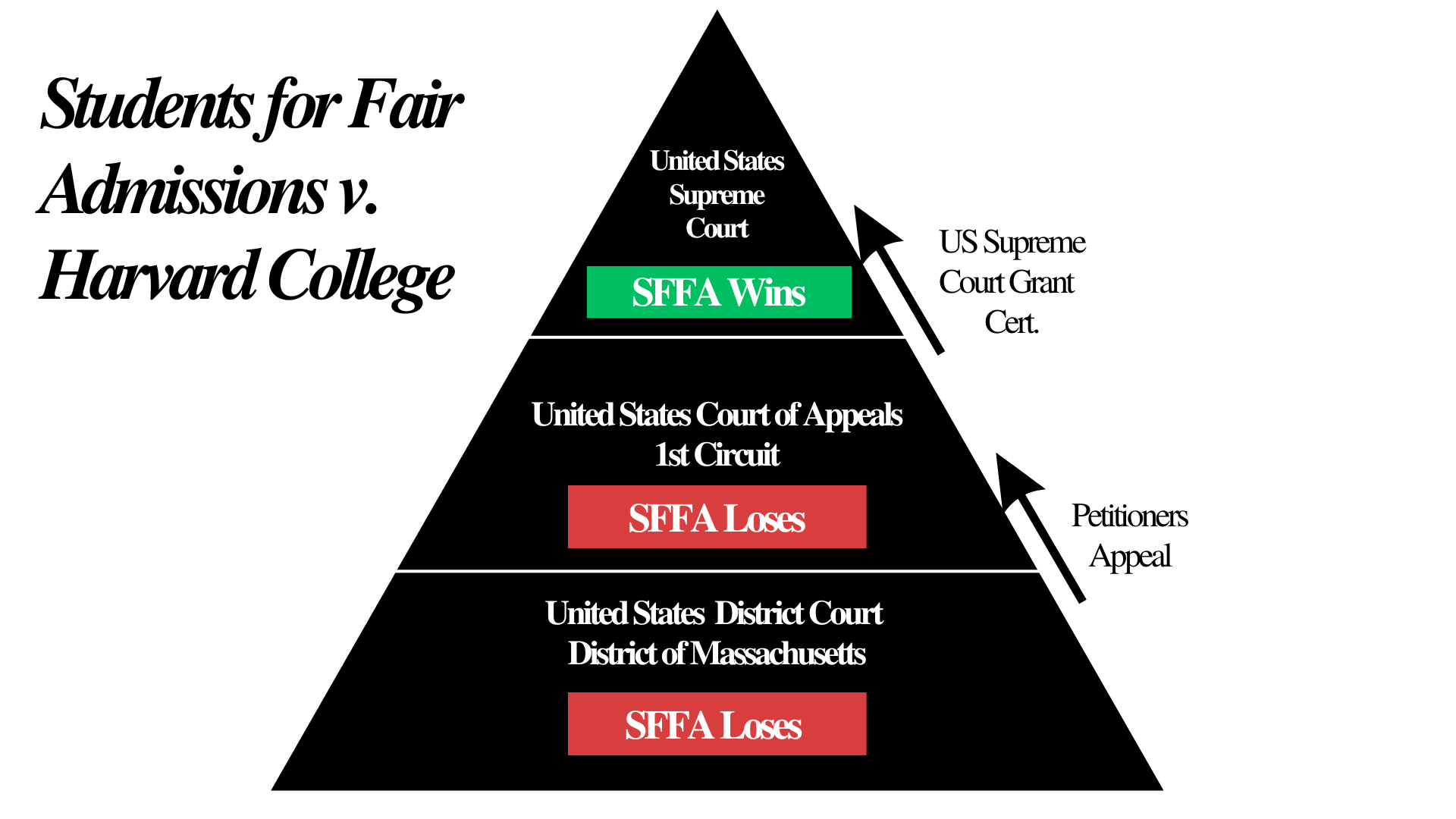

Students for Fair Admissions is a nonprofit group opposed to affirmative action that challenged Harvard and UNC's race-conscious admissions policies, citing violations of constitutional and civil rights.

In 2014, SFFA filed a lawsuit against Harvard, alleging racially and ethnically discriminatory practices in its undergraduate admissions program. SFFA represented a group of Asian-American plaintiffs who were rejected by Harvard. SFFA also filed a similar lawsuit against UNC.

Although SFFA initially lost in lower courts, the organization pursued appeals to the Supreme Court.

UC System

Affirmative action supporters contend that race-blind admissions will decrease the diversity of the student body. One significant piece of evidence was the diversity trends of the University of California system following California’s ban on race-based preferences.

After California amended its State Constitution to prohibit race-conscious college admissions in 1996, Justice Sotomayor argues, freshmen enrollees from underrepresented minority groups dropped “precipitously” in California public universities. “Rates of admission of underrepresented groups dropped by 50% or more,” Sotomayor contends.

Dissent

Where Justice Jackson was recused, Justice Sotomayor along with Justice Kagan wrote dissenting opinions on the ruling on Harvard. Justice Jackson also dissented from the ruling on the UNC case.

Justice Sotomayor criticized the Court for imposing its preferred college application format on the nation, claiming it acted as “college administrators” rather than a court of law applying precedent.

She argued that racial identity informs students' viewpoints and experiences uniquely and that the compelling interest in student body diversity is grounded in principles of “academic freedom”.

“...Underrepresented minority students are more likely to live in poverty … [are] more likely to attend schools with less qualified teachers, less challenging curricula, lower standardized test scores, and fewer extracurricular activities and advanced placement courses ... are less likely to attend preschool and other early childhood education programs that increase educational attainment … All of these interlocked factors place underrepresented minorities multiple steps behind the starting line in the race for college admissions” - Justice Sotomayor, SFFA v. Harvard

Sotomayor also warned against SFFA's proposed plan, which was designed to increase preferences for low-income applicants and eliminate the use of race and legacy preferences. She cautioned that such a plan would decrease black representation “by about 32%.”

Sotomayor also criticized the majority court's admissions data, deeming it “misleading”, and pointed out that admissions for all racial minorities, including Asian American students, have increased significantly (roughly five-fold) since 1980.

One Type of Institution Can Still Use Affirmative Action: Military Academies

The majority opinion, authored by Chief Justice Roberts, exempted military academies from the ruling. Government-funded service academies, such as West Point, will be allowed to continue their affirmative action programs. The Court argued that service academies were not involved in the Harvard and UNC cases and emphasized the compelling interests served by affirmative action at military academies.

The government's stance extends affirmative action not only to military academy institutions but also to applicants commissioned in civilian universities, such as Harvard's Reserved Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) programs.

“The United States as amicus curiae contends that race-based admissions programs further compelling interests at our Nation’s military academies. No military academy is a party to these cases, however, and none of the courts below addressed the propriety of race-based admissions systems in that context. This opinion also does not address the issue, in light of the potentially distinct interests that military academies may present.” - Footnote, SFFA v. Harvard

What Does This Mean for Future Applicants?

While the Supreme Court overturned decades of precedent, it acknowledged the importance of race in storytelling within college applications. Chief Justice Roberts argued colleges may consider “an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” Simply having a ‘checkbox’ of an applicant’s racial identity can no longer be a determining factor in whether an applicant receives acceptance to the institution.

In 2022, Pew Research Center published that nearly 74% of people in the U.S. stated that race or ethnicity should not be considered in college admissions.

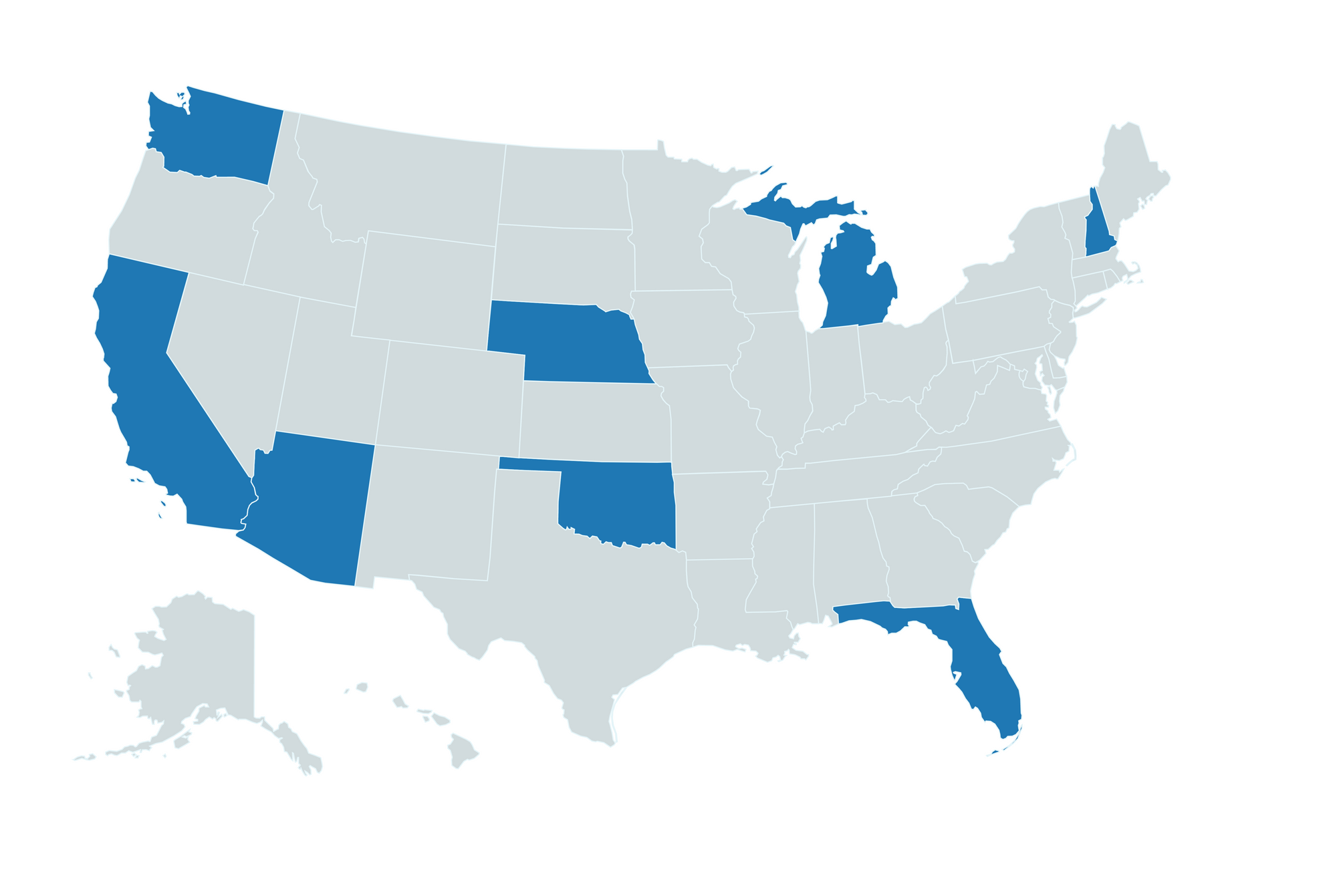

Although the rulings in SFFA v. Harvard and SFFA v. UNC significantly limited the role of race in college admissions, other preferences such as legacy or athletic considerations may continue to be followed. Prior to the national ruling, eight states had already banned race-based preferences, including California (1996), Florida (1999), Michigan (2006), Nebraska (2008), Arizona (2010), New Hampshire (2012), Oklahoma (2012), and Idaho (2020).

“Today, the Court concludes that indifference to race is the only constitutionally permissible means to achieve racial equality in college admissions.” - Justice Sotomayor, SFFA v. Harvard