The recent case, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, explores the application of using religious speech to refuse service to same-sex marriages.

Many states, including New York, have statutory laws that extend civil protections to other protected classes such as same-sex couples. In the State of Colorado, businesses open to the public cannot discriminate against groups of people -- protected classes -- based on a customer’s religion, sexual orientation, race, sex, disability, or other characteristics protected under the statute (C.R.S. § 24-34-601). But what happens when a business owner refuses to provide services to a protected class on religious grounds?

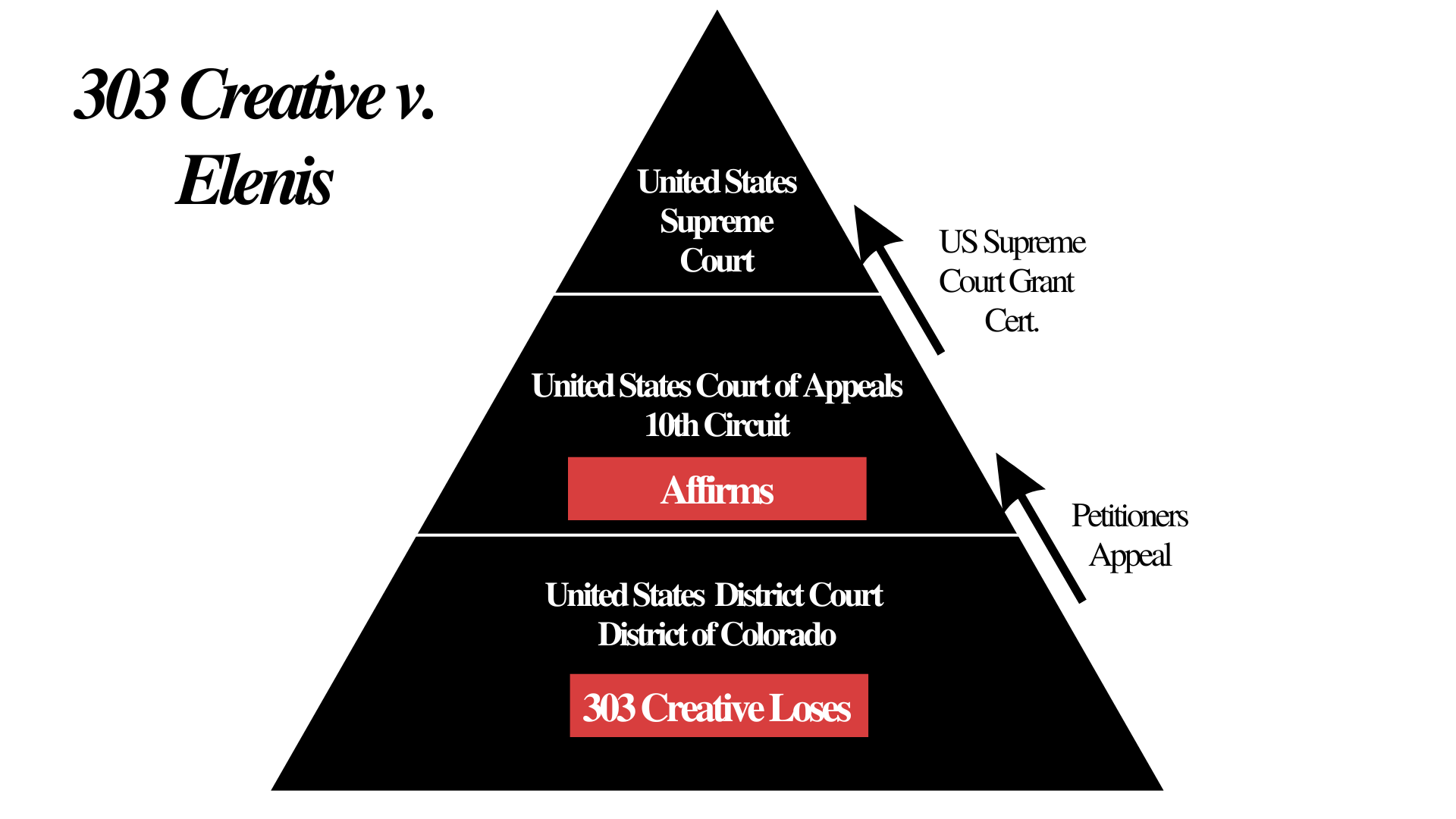

Business founder Lorie Smith owns a for-profit, public-accommodated business that provides web design services to members of the public. Named 303 Creative, Smith’s business had expanded to a niche in creating and designing wedding websites for customers. However, as a Christian, Smith claims that her religious stance would not be consistent if she had provided services to same-sex couples. When Smith wanted to create a notice of dispreference to provide services for same-sex couples, she was cautious that such notice would violate Colorado’s AntiDiscrimination Act (C.A.D.A). Because 303 Creative was registered in the State of Colorado and her principal place of business resided in Colorado, Smith had to abide by state law. Before the State of Colorado could enforce CADA, Smith sued the State of Colorado for violating her religious rights. Because Smith claimed that the state violated her constitutional rights (First Amendment’s Freedom of Speech), Smith, represented by Alliance Defending Freedom, sued in federal district court in 2016. In the case, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, the petitioners, 303 Creative, is suing Audrey Elenis, the Director of the Colorado Civil Rights Division which enforces CADA.

The federal district court postponed its decision until the Supreme Court decided on a similar, earlier discrimination case. In 2018, the Supreme Court case, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, became a recent precedent that gave grounds for the district court to rule against Smith. In Masterpiece Cakeshop, a cake owner refused service to a same-sex couple because of his religious stance in 2012. The cake owner argued that his expertise in creating cakes was a form of art that was protected by the First Amendment. The same-sex couple filed a complaint with the State of Colorado Civil Rights Commission -- the governing enforcement agency for state discrimination cases. In hearing the case, the Civil Rights Commission sided with the same-sex couple which the cake owner later sued. After multiple appeals, the Supreme Court decided to hear arguments but gave a decision that asked a different question. Instead of questioning if a refusal of service to same-sex couples was discriminatory or allowed based on religious beliefs, the court asked whether Colorado’s AntiDiscrimination Law violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. This question was established since the argument was that Colorado’s Civil Rights Commission acted religiously hostile to the cake owner when hearing the issue. Although the Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision and sided with the cake owner, the issue of the Supreme Court’s reasoning was based on procedural fairness.

In the majority opinion, the Supreme Court argued that Colorado Civil Rights Commission did not afford neutrality concerning the cake owners' religious objections. In fact, prior to the Commission’s decision, the Supreme Court looked at 3 other past cases where the Commission granted similar refusal of services that were considered offensive. Therefore, the Supreme Court reasonably thought that the Commission's decision was a result of religious hostility. Therefore, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission did not entirely answer the conflict between the religious free speech of the cake owner and the civil rights of the same-sex couple. Although the Supreme Court did acknowledge the authority of the State to protect equal access to sales, the decision was different. Instead, the Court reversed the lower court's ruling on the fact that the State did not consider a neutral stance on the cake owner's religious speech.

“Whatever one may think of the events that gave rise to this case, the baker was entitled to a neutral decision maker who would give full and fair consideration to his religious objection. The delicate question that when the free exercise of religion must yield to an otherwise valid exercise of State power needed to be determined in an adjudication in which religious hostility on the part of the State itself would not be a factor in the balance the State sought to reach. That requirement was not met here.”

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission was a similar analogy to 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis but had slightly different interpretations. For one, one may question whether a custom website design is a form of art than creating custom cakes. Secondly, 303 Creative did not have a history of discrimination and did not test such discrimination against same-sex couples. Instead, Smith considered suing for her constitutional rights before she officially put up a notice about her religious objections. This is different from Masterpiece because the cake owner sued after the state -- Colorado Civil Rights Commission -- found it to be discriminatory. In 303 Creative, the Supreme Court will seek to answer whether applying CADA, a public accommodation law can compel an artist to speak or remain silent. Its precedent in Masterpiece did not answer the question.

Court's Question: whether applying a public-accommodation law to compel an artist to speak or stay silent violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

Although religion is an important element, the question for the Court reflects speech in broad terms. In general, the First Amendment of the United States Constitution protects individuals from government infringement on speech. Government infringement includes laws that may infringe on an individual’s right to expression. In 303 Creative, Smith asserts that her website creation and the graphic designs she makes are a form of protected speech. Smith contends that CADA will compel her to create speech (websites, graphic designs) that would violate her First Amendment rights. Over 75 amicus briefs have been filed, 20 of which are from state governments supporting Smith. One of the briefs was written by United States Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and co-signed by 20 senators.

“This case is yet another example of states ‘wield[ing]’ public accommodation laws ‘as a sword’ to compel individuals to speak or stay silent on controversial issues.”

In the brief, Ted Cruz argues that CADA forces Smith to create a website against “her will”. Cruz explains how CADA in forcing Smith in creating speech, betrays her religious convictions. Cruz advises that such coercion is grounds for applying the highest judicial scrutiny against the state. Cruz argues that CADA should not survive under strict scrutiny because the state has no compelling interest nor is CADA narrowly tailored enough. The state can alternatively prevent discrimination, Cruz states, by exempting “message-based services from CADA’s prohibitions”. Therefore, the brief asked the Court to rule in favor of Smith and reverse the lower court’s decision.

“Compelling an individual to use her artistic and intellectual capabilities to create a message she opposes is the most odious form of compelled expression.”

One of the main critiques of Smith’s argument is whether website design constitutes as protected speech. In Tinker v. Des Moines, the broad term, speech, is considered to be visual expressions. In Tinker, the Supreme Court considered anti-war armbands worn by students as a form of protected speech. From the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, the 3-judge panel ruled that Smiths' website designs were a form of protected speech. However, the Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s decision because the State of Colorado still had a compelling interest to provide equal access to goods and services. Similarly, Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser argues that CADA is designed to regulate sales and not to restrict speech. Weiser contends that selling is not a form of expressive speech but a sale of a good or service.

“What a business chooses to sell to the public remains entirely up to the business. Once a business offers something to the public, however, the law ensures it must offer it to any customer regardless of their race, religion, sexual orientation, or other protected characteristic.”

Multiple amicus briefs against Smith have contested similar arguments. From the American Civil Liberties Union, David Cole believes that the state should not compel any artist to create expressive speech that an artist disagrees with. Cole, however, supports Colorado’s law because of 2 reasons. One, Cole argues that CADA treats every business equally. Public accommodations laws, Cole states, do not dictate a business actor’s speech and therefore do not violate the First Amendment. Secondly, Cole argues that it is voluntary for an artist to open his or her business to the public.

“The photographer Annie Leibovitz, for example, does not offer to take photographs of anyone who offers to pay her fee but chooses her subjects. She is perfectly free to photograph only white people or only Buddhists. … The choice to benefit from the public marketplace comes with the legal obligation to equally serve members of the public. And requiring businesses that offer expressive services in the public marketplace to follow the same rules as all other businesses does not violate the First Amendment.”

Likewise, the New York State Bar Association also wrote in favor of the state. In its brief, the New York State Bar Association displayed historical evidence that supports governmental compelling interest in enforcing anti-discrimination laws. In New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n, Inc. v. Bruen, the Supreme Court emphasized how the government must point to historical events about the “reach of First Amendments’ protections”. The Bar argues that such First Amendment protections do not override the state’s compelling interest in combatting discrimination.

It is unclear whether the Supreme Court will rule in favor of Smith or affirm the lower court’s decision. It is also important to understand the implications of this case’s ruling. If the court rules in favor of Smith, would public accommodations laws have to reconsider services that create speech? Would it be constitutional to refuse service to a protected class because it creates speech? Conversely, if the court affirms the lower court’s ruling, could states create more strict public accommodations laws that restrict the refusal of speech-creating services like photography? David Cole states that a ruling against the public accommodations law would have dangerous implications.

“Otherwise, interior decorators, landscape architects, tattoo parlors, sign painters and beauty salons… whose services contain some expressive element, would all be free to hang out signs refusing to serve Muslims, women, the disabled, African Americans or any other group.”